How Defined Benefit Pensions Support a Quality Public Sector Workforce in Marin County

The Marin Public Pension Series is a three-part issue brief series intended to provide policymakers and the public with an informed perspective on the value, cost, and broader social implications of defined-benefit (DB) pensions for public employees in Marin County, California. Brief #1 examines the economic value of defined benefit pensions for public employees, employers, and residents in Marin County. Brief #2 addresses the cost and sustainability of public employee pensions. Brief #3 highlights the role of public defined-benefit pensions in reducing retirement wealth inequality by race, gender, and education compared to 401(k)-style plans.

Highlights

- Marin County public employees—i.e., state and local government employees who work in the county—receive significantly lower average pay than private sector employees given their education.

- Public employment in Marin County is dominated by local government employment, a majority (55%) of which is in education and health services. Public K-12 schools alone account for 34%. Other significant sectors are general government (13.5%), justice and public safety (11%), and transportation, warehousing and utilities (12%).

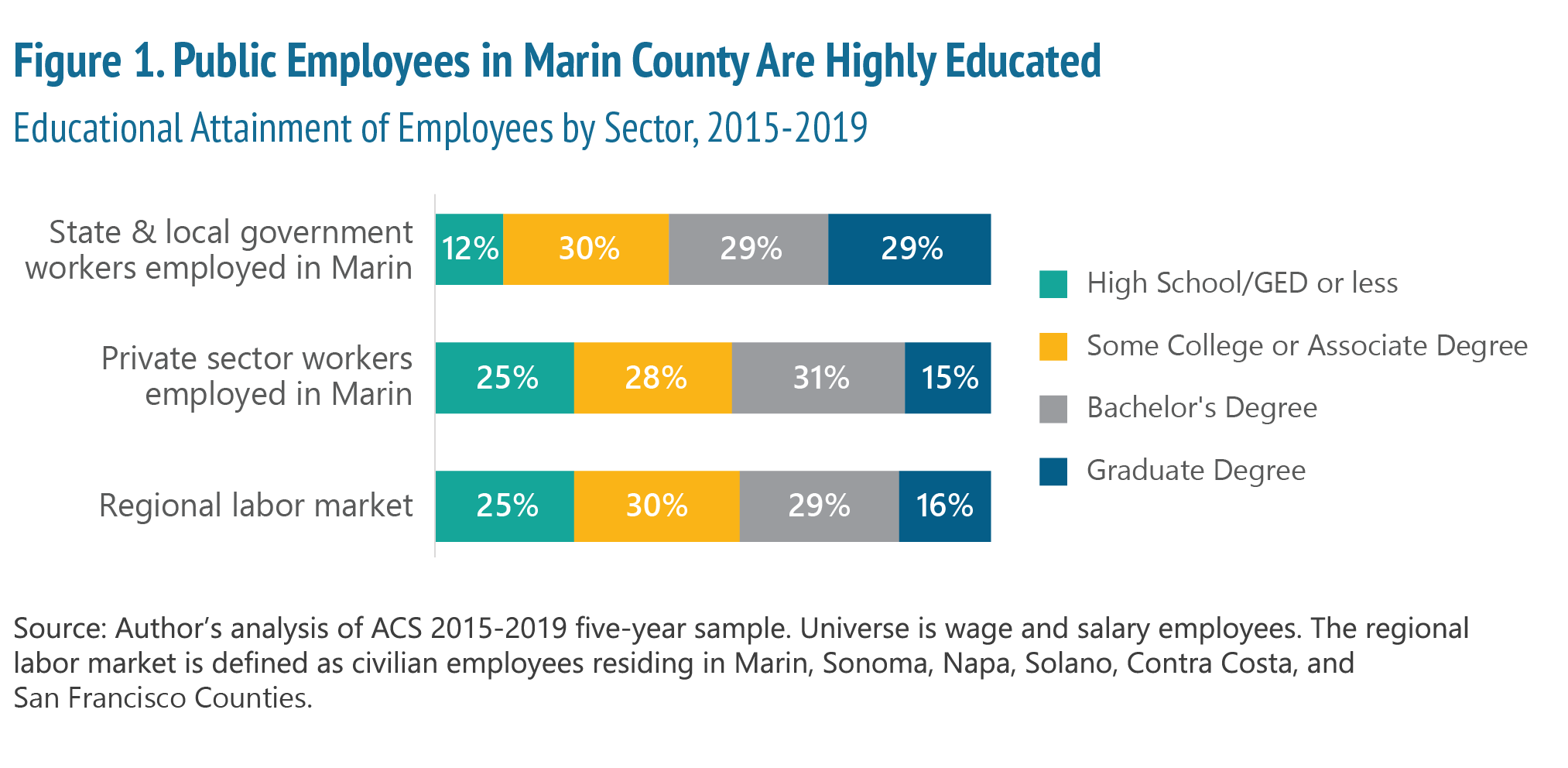

- Public employees working in Marin County are more likely to have at least a bachelor’s degree (58%) than private sector employees (46%) and the regional labor market as a whole (45%). They are also nearly twice as likely to have a master’s, professional, or doctoral degree compared to private sector employees in Marin (29% vs. 15%).

- Relative to private sector workers, the wage penalty for public employees in Marin County is 15% for those with bachelor’s degrees and 39% for those with advanced degrees. Those with associate degrees or high school degrees earn a wage premium, but this is outweighed by the wage penalty for workers with higher educational attainment.

- Even without accounting for differences in education, full-time employees in Marin County earn 8% less on average in the public sector than in the private sector.

- When educational attainment is taken into account, the average wage income of full-time, year-round public employees working in Marin County is 17% lower than that of similarly educated private sector employees.

- Higher expenditures on benefits as a percentage of pay help offset the public sector pay penalty. Nonetheless, average total compensation is approximately 5% lower in the public sector than in the private sector among full-time, year-round employees in Marin County. In addition, data from a recent study suggests that California teachers overall face an estimated 7% pay penalty given their experience and education, after taking benefits into account.

- Public pensions help offset the public sector pay penalty in a fiscally efficient manner, by providing adequate retirement income at a fraction of the cost that 401(k)s would require for the same benefit.

- Pensions deliver more retirement income per dollar of contribution than 401(k)s due to longevity risk pooling as well as higher investment returns from a longer investment horizon, lower fees, and professional investment management.

- Most public school teachers in California, including those in Marin public schools, will receive at least 50% higher retirement income from CalSTRS than they would from an idealized 401(k) that receives the same contributions. Full-career educators, who make up nearly half the teacher workforce, will receive benefits equal to 49% of their final salary—twice the income that they would get through a typical 401(k) with the same contributions.

- A full-career employee covered by CalPERS will receive twice the retirement income that they could get from a 401(k) with low fees and no investment mistakes that receives the same contributions as their pension.

- For teachers hired after 2014, CalSTRS retirement, death, and disability benefits accrued in FY 2021-22 cost 18.086% of payroll. Teachers contribute more than half of this cost, 10.205% of their pay. For the average teacher, this provides a secure retirement income that would cost about 35% of payroll to provide through a typical 401(k).

- By attracting and retaining skilled workers, public pensions contribute to public service quality, including quality public education.

- Turnover data clearly shows that CalSTRS helps keep experienced teachers in the classroom until at least age 55, the earliest age at which they can claim their pension.

- Three out of four teachers covered by the CalSTRS pension will serve at least 20 years. Nearly half will serve a 30-year career.

Introduction

This is the first in a three-part issue brief series intended to provide policymakers and the public with an informed perspective on the value, cost, and broader social implications of defined benefit (DB) pensions for teachers, nurses, firefighters, and other workers who provide essential public services to the residents of Marin County. This brief examines the economic value of DB pensions—which provide secure monthly retirement income based on salary and years of service—for public employees, employers, and residents in Marin County.

Based on analyses of Census data and public pension data, this brief highlights a critical fact that is often overlooked in debates about public employee compensation and benefits. On average, public employees are paid less than private sector employees given their education. In Marin County as well as in California as a whole, workers with four-year college degrees and advanced degrees make up a much larger share of the state and local government workforce than the private sector workforce. Conversely, a smaller share of public sector employees have no college education, and even these workers are more likely to have specialized occupational training than in the private sector. Yet in Marin County, average public sector pay is lower than average private sector pay, both with and without accounting for differences in educational attainment.

In this context, DB pensions play a critical role in the compensation of public employees, offsetting part of the public pay penalty in a financially efficient manner. Pensions not only provide predictable retirement income that employees highly value; they do so at a much lower cost compared to 401(k)s. DB pensions are also highly effective in lowering turnover and retaining experienced workers, which is correlated with quality public services including public K-12 education. This provides significant value to employees, employers, and the public.

Without DB pensions, public employers would have to significantly increase salaries for the majority of positions in order to maintain workforce quality, and turnover of experienced employees would increase.

Retirement Benefit Types

Defined Benefit (DB) pensions provide lifetime retirement income, usually based on the employee’s final average salary and years of service. While most public pensions are jointly funded by employers and employees, the employer is ultimately responsible for promised benefits.

Defined Contribution (DC) plans, such as 401(k)s, are individually managed investment accounts. The employer and/or employee contribute, depending on the plan. While the plan provides investment fund options at the employer’s discretion, the employee assumes all investment risk.

I. Public Employees Working in Marin County Are More Educated and Experienced Than Private Sector Workers

Before comparing the pay of public and private sector workers in Marin, it is important to understand the ways in which public and private sector jobs and workers differ. In particular, a significantly higher share of jobs in the public sector involve occupation-specific training, four-year degrees, and/or advanced degrees.

Definition of Public Employee

In this brief, public employees are defined as state and local government employees. Local government includes cities, counties, local law enforcement, school districts, community college districts, utility districts, transportation districts, and other local and regional public agencies. Outside of Sacramento, California state government employment includes the state court system, state law enforcement, other public administration functions, and the California State University and University of California systems.

Public employment in Marin County consists primarily of local government employment, more than half of which consists of education and health services (55%), according to the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (Table 1). Public elementary and secondary schools alone account for 34% of local government jobs. Other significant sectors are general government (13.5%), justice and public safety (11%), other public administration (7.5%), and transportation, warehousing, and utilities (12%). State government employment in Marin County is about one-fifth the size of local government employment, and consists primarily of the court system, law enforcement, and corrections (Table 1).

Data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey shows that Marin County’s public sector workforce is significantly more educated than its private sector workforce (Figure 1). This is unsurprising given the makeup of public sector jobs; both education and health services entail a significant share of workers with four-year college degrees or advanced degrees. A large majority, 58%, of state and local government employees in Marin have at least a bachelor’s degree, compared to 46% of local private sector employees and 45% of workers in the regional labor market. (Based on Census commuting data, the regional labor market is defined in this brief as civilian wage and salary workers in Marin, San Francisco, Sonoma, Napa, and Contra Costa Counties.[1]) In fact, state and local government employees in Marin skew heavily towards those with advanced degrees: 29% have a master’s degree, professional degree, or doctorate, compared to 15% of local private sector wage and salary workers and 16% of workers in the regional labor market.

Only 12% of state and local government employees who work in the county have no college education, compared to 25% of private sector employees working in Marin and 25% of the regional labor market. Notably, many public employees without a college education are in occupations that require significant training, for instance firefighters, police, public transit operators, and utility workers.

In addition, the typical public employee who works in Marin County is more experienced than the typical private sector employee, with a median age of 49 years—7 years older than the median age of 42 for both local private sector employees and the regional labor market (Table 2).[2]

II. Public Employees in Marin County Face a Significant Wage Penalty

In sharp contrast to the notion that public employees are overpaid, Census data shows that the average pay for public employees in Marin County is 8% less than that of private sector employees, despite greater experience and higher levels of education. When educational attainment is factored in, public employees earn 17% less than private sector employees.

Figure 2 compares the annual average wage income of all full-time, year-round workers employed in the public sector and private sector in Marin County, as well as workers in the regional labor market. The chart also compares pay for those with four-year college degrees and advanced degrees. In 2015-2019, full-time, year-round public employees in Marin County had an annual average wage income of $83,300 in 2019 dollars—8% less than the local private sector average of $90,500.[3] In addition, workers employed in Marin County whose highest degree was a bachelor’s earned 15% less in the public sector than in the private sector ($92,400 vs. $109,100). Those with a master’s, Ph.D., or other advanced degree earned 39% less on average in the public sector than in the private sector ($94,600 vs. $154,000).

These negative pay differentials for public employees in Marin County cannot be explained away by unusually high wages at the top in the Bay Area tech economy inflating private sector average (mean) pay. The annual income of middle-earning workers (i.e., median wage income) is also significantly lower in the public sector for those with bachelor’s and advanced degrees.[4] Furthermore, Marin County and the North Bay do not figure significantly in the Bay Area tech economy.

When educational mix is taken into account, the total wage income of full-time, year-round state and local government employees in Marin County is 17% less than it would be based on local private sector pay scales (Figure 3). In the private sector, a similarly educated workforce would have averaged $100,400 in annual pay in 2015-2019, compared to the actual public sector average of $83,300.

While public sector employees are not collectively “overpaid,” their wages are much less unequal than in the than private sector. Due to sample size constraints in the ACS, average pay for government workers without four-year college degrees was not included in Figure 2. However, regional data indicates that in the public sector, workers with advanced degrees earned $2.00 for every dollar earned by and those with no those with no college education, compared to $3.60 in the private sector.[5] And while workers without 4-year college degrees benefit from a pay premium—10% for those with no college education, and 7% for those with some college or an associate degree—this is significantly outweighed by the large wage penalty for the majority of public employees with bachelor’s and advanced degrees.

Teachers in particular experience a significant pay penalty, according to recent research, due in part to the historic devaluation of female-dominated occupations. California teachers face an average 15.5% pay penalty compared to other college educated workers with similar experience, according to an analysis from the Economic Policy Institute.[6] A pay penalty persists even when only comparing female teachers to other female college educated workers. The study found that nationally, adding in employee benefits such as health insurance and retirement benefits offset only about half of the teacher pay penalty. Extrapolating from national data, this suggests that California teachers make about 7% less than other college educated workers after accounting for benefits.

In general, retirement benefits, health care, paid time off, and other fringe benefits offset much—but not all—of the public sector pay penalty in Marin County. In 2018, benefits for state and local government employees averaged 39% of total compensation, or 64% of base pay, in the Pacific Census Division (California, Oregon, Washington, Alaska, and Hawaii).[7] Benefits for private sector employees averaged 30% of total compensation, or 43% of base pay in the Pacific Division, as well as in the San Francisco Bay Area.[8] Despite the higher benefit expenditures, total estimated compensation for Marin public employees is about 5% less than that of their public sector counterparts.[9]

III. DB Pensions Help Offset the Public Sector Pay Penalty in a Fiscally Efficient Manner

If employees face a significant wage penalty in the public sector, the valuable retirement income security provided by DB pensions partially offsets this penalty in order to attract skilled workers.

Importantly, DB pensions provide meaningful retirement income at significantly less cost than a 401(k). This is due to key structural efficiencies in DB pensions: longevity risk pooling, higher investment returns, and lower fees. The National Institute on Retirement Security estimates that for a teacher who serves out a full career in public schools, DB pensions provide retirement income at half the cost of a typical 401(k) (Figure 4):[10]

- DB pensions pool longevity risk. What this means is that public pensions only need to accumulate enough assets to generate retirement income for the average life expectancy of their members. In contrast, workers who rely solely on a DC plan must save enough to last well past life expectancy—for instance, to the 75th or 90th percentile—or else risk running out of money with years of life left. Private insurance annuities can guarantee lifetime income, but are expensive to purchase in part due to low interest rates, but also because of adverse selection: people who buy life annuities are also likely to live longer than average, and annuity prices reflect this.

- DB pensions invest over a longer time horizon than individuals. Public pensions have a mix of entry-level, mid-career, and older workers who contribute to the fund along with their employers, and retirees who draw benefit payments. Therefore, they can keep the majority of their assets invested in stocks as long as the plan remains open to new members. In contrast, individual 401(k) investors must reduce the risk their investment portfolio by shifting from stocks to bonds as they approach retirement age, which means lower expected returns.

- Public sector DB pensions earn higher average returns than individual 401(k) investors due to professional investment management, and lower fees.

- Professional investment management: Public pension funds are invested by professional money managers in accordance with investment policies and goals set by the pension trustees. In contrast, research shows that individual investors tend to chase returns, buying expensive stocks when the market is up and panic-selling when the market is down. In other words, they buy high and sell low. A recent study by Morningstar found that individual investor returns averaged 45 basis points (.45%) below market performance due to poor timing decisions alone.[11] In contrast, investment returns for California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS), California State Teachers’ Retirement System (CalSTRS), and other public pensions in California closely follow the market.

- 401(k)s incur higher fees than DB pensions. A Boston College Center for Retirement Research study found that DB plans outperformed real-world 401(k)s by an average of .7% annually, and that lower investment returns and higher fees contributed to this difference.[12]

- Other factors further erode 401(k)s compared to pensions. A significant share of 401(k) assets leak out through early withdrawals, as participants treat them like emergency funds rather than a retirement nest egg. Account assets are particularly vulnerable during job changes.

A series of studies by the Labor Center, validated by professional actuaries, found that the vast majority of teachers who are currently covered by CalSTRS (85%) will accrue higher benefits under their DB pension than through an idealized 401(k), given the same stock market conditions and contributions.[13] The latest of these studies found that 75% of teachers will serve at least 20 years.[14] Based on an updated analysis, Figure 5 illustrates the percentage of final salary replaced by CalSTRS, an idealized 401(k), and a realistic 401(k) for a teacher hired at age 30. After 20 years of service, the CalSTRS pension will replace 20% of their final salary. This is 54% higher than the 13% income replacement rate from an idealized 401(k) with low fees and no investor mistakes under similar financial market conditions as the pension.[15]

For the same teacher who serves a full 30-year career, the CalSTRS pension will replace 49% of their final salary, compared to 29% from the idealized 401(k) and 25% from a more realistic 401(k) with typical individual investor behavior. In other words, career teachers will receive 69% higher retirement income from CalSTRS than they would from an idealized 401(k), and twice the amount from a typical 40(k), for the same cost.

For teachers hired after 2014, CalSTRS retirement, death, and disability benefits accrued in FY 2021-22 cost 18.086% of payroll. The retirement benefit is 2% of final average salary at age 62 for each full year of service. Teachers contribute more than half of this cost, 10.205% of their pay. For the average California teacher—who will serve 27 years and leave teaching in their early 60s—this provides a secure retirement income that would cost about 35% of payroll to provide through a typical 401(k).

Teachers—three-quarters of whom are women—are particularly long-lived, so the guarantee and longevity risk pooling in DB pensions is especially valuable to them. Importantly, California public school teachers are not covered by Social Security. The Social Security benefits they might earn through other employment are steeply reduced by the Government Pension Offset. This means that the CalSTRS pension is their only meaningful source of guaranteed retirement income.

CalPERS, which covers non-educator school employees and most other local public government employees in Marin County, offers similar efficiency for providing retirement income (Figure 6). For a non-safety public agency employee hired at age 30 after 2012, CalPERS will provide 21% of pre-retirement income after 20 years of service, and 49% after 30 years. An idealized 401(k) that receives the same contributions would provide 18% of income at 20 years, and 26% of income at 30 years. A realistic 401(k) would replace just 23% of income after a full career, for the same cost as the CalPERS pension. This means that for a career employee, CalPERS provides 88% higher income than an idealized 401(k) and more than twice as much income as a realistic 401(k).[16]

IV. DB pensions help public employers recruit and retain employees—especially teachers

DB pensions help public employers attract highly skilled workers from the private sector.[17] In addition, pensions offer a powerful economic incentive for experienced workers to stay until retirement age. They also encourage orderly exit of workers who are past their peak productivity. A study from the Boston College Center for Retirement Research found that workers in DB plans are more likely to stay with the same employer until retirement age than workers in DC plans.[18]

Nowhere is the retention effect of pensions clearer than in public education. Our previous studies of CalSTRS found that teacher career patterns are tightly linked to benefit policy.[19] Early career turnover is high in the teaching profession, but in California, attrition rates drop dramatically after three years or so and stay at very low levels through mid-career (Figure 7). Attrition starts to increase at age 55, when teachers become eligible for reduced early retirement benefits. The typical California teacher will leave after full retirement age (62) with 27 years of service.[20] Consequently, three out every four public school teachers covered by CalSTRS will work at least 20 years, and 47% will work a full 30-year career in public education in the state. A separate study of teacher pensions in six states found a similarly tight link between retirement benefit policy and teacher retention.[21]

Given that education quality is positively correlated with teacher experience and negatively correlated with teacher turnover, these data suggest that the CalSTRS pension contributes to quality public education. Replacing the pension with a 401(k) would not only jeopardize the long-term financial security of public school teachers, but also increase mid-career teacher turnover and thereby diminish education quality.

Conclusion

Defined benefit pensions are a critical component of compensation for public employees in Marin County, who are paid less on average than private sector employees despite being significantly more educated and experienced. When both educational attainment and benefit costs are accounted for, the total annual compensation for full-time public employees in Marin County is about 5% less than for similarly educated private sector employees. As an important part of the public sector employee benefit package, CalSTRS, CalPERS, and other public pensions help offset the pay penalty in a cost-efficient manner, providing retirement benefits at roughly half the cost that it would take to provide the same benefits through a typical 401(k). In addition, pensions clearly help retain experienced public employees, especially in public schools where teacher retention contributes to quality education.

Public pensions are advantageous in other ways for state and local employees working in Marin as well as for the broader public. For public employees, pensions are an increasingly important vehicle for retirement wealth accumulation given that home ownership—another major source of financial security in retirement—is out of reach for younger teachers and many other essential public service workers. Local median home prices range from $750,000 in Sonoma County to $1.8 million in Marin County as of August 2021.[22] Assuming a 20% down payment, a house in Sonoma County requires an income of $150,000 a year—about twice the annual income of a typical full-time public employee who works in Marin. The house in Marin County requires $320,000 annual income.[23]

For the public, state and local pensions generate positive economic spillovers by providing steady monthly retirement income through economic booms and busts. CalPERS payments generated $114 million in economic activity in Marin County in fiscal year 2019-2020.[24] A 2014 study by CalSTRS found that $98 million in total economic benefit resulted from $71.7 million in benefit payments due to the economic ripple effects of spending.[25] Statewide in California, each dollar of pension benefit paid out in 2018 resulted in $1.54 in total economic output, and total pension payments supported nearly 400,000 jobs that paid $25.4 billion in wages.[26] Given that 64% of public pension benefits in California were paid by investment returns and 12% by employee contributions, each dollar of taxpayer contributions to state and local pensions generated $6.50 in total economic output.

In summary, public DB pensions provide significant value for employees, employers, and taxpayers in relation to their cost. They are also one of the last bulwarks of middle-class retirement income security, at a time when inadequate and highly unequal benefits in the private sector 401(k) system have generated a national retirement savings crisis and calls for structural reform.[27] Rather than dismantle what remains of worker retirement security, public policies should focus on strengthening public pensions for long-term sustainability and ensuring that private sector workers have secure and adequate retirement income.

About the Author

Nari Rhee, Ph.D., is the director of the Retirement Security Program at the UC Berkeley Center for Labor Research and Education.

Acknowledgements

This brief was made possible in part by the North Bay Labor Council’s support for the Labor Center’s Retirement Security Program. However, the views, findings, and any errors or omissions in this brief are the sole responsibility of the author.

Suggested Citation

Rhee, Nari. How Defined Benefit Pensions Support a Quality Public Sector Workforce in Marin County. Center for Labor Research and Education, University of California, Berkeley. October 2021.

https://laborcenter.berkeley.edu/marin-pension-brief-no-1/.

Endnotes

[1] According to the author’s analysis of commute data in the 2015-2019 ACS sample, Sonoma, San Francisco, Solano, and Contra Costa Counties are the largest sources of commuters into Marin County. Napa County, which provides a small share, was included for the sake of geographical contiguity.

[2] Author’s analysis of ACS 2015-2019. Universe consists of full-time, year-round wage and salary employees.

[3] Percentage differences are calculated from unrounded pay data.

[4] Based on the same data, the median annual wage income of full-time, year-round public employees was 11% lower for those with a BA or BS, and 21% less for those with advanced degrees, compared to the private sector.

[5] Author’s analysis of ACS 2015-2019.

[6] Sylvia Allegretto and Lawrence Mishel, “Teacher pay penalty dips but persists in 2019,” Economic Policy Institute, September 2020. https://www.epi.org/publication/teacher-pay-penalty-dips-but-persists-in-2019-public-school-teachers-earn-about-20-less-in-weekly-wages-than-nonteacher-college-graduates/.

[7] U.S. Census Bureau, National Compensation Survey/Employer Costs for Employer Compensation.

[8] Ibid.

[9] It is important to note that the pay analysis in this brief does not account for certain factors that might change the public sector compensation gap in either direction. For instance, it does not analyze the fields in which workers have bachelor’s or advanced degrees, nor does it consider non-academic credentials that many blue-collar public sector employees have. It also does not account for differences in pay and benefits by firm size, even though government employment is analogous to large firm employment which is associated with greater pay and benefits.

[10] William B. Fornia and Nari Rhee, “Still a Better Bang for the Buck: An Update on the Economic Efficiencies of Defined Benefit Pensions,” National Institute on Retirement Security, December 2014. https://www.nirsonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/bangforbuck_2014.pdf.

[11] Russel Kinnel, “Mind the Gap 2019,” Morningstar, August 15, 2019. https://www.morningstar.com/articles/942396/mind-the-gap-2019.

[12] Alicia H. Munnell, Jean-Pierre Aubry and Caroline V. Crawford, “Investment Returns: Defined Benefit vs. Defined Contribution Plans,” Issue Brief #15-21, Center for Retirement Research at Boston College. https://crr.bc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/IB_15-211.pdf.

[13] Nari Rhee and William B. Fornia, “Are Teachers Better off with a Pension or 401(k)?,” UC Berkeley Center for Labor Research and Education, 2016, https://laborcenter.berkeley.edu/pdf/2016/California_Teachers_Pension_401k.pdf; Nari Rhee and William B. Fornia, “How Do California Teachers Fare under CalSTRS? Applying Workforce Tenure Analysis and Counterfactual Benefit Modeling to Retirement Benefit Evaluation,” Journal of Retirement v5n2:42-65, Fall 2017; Nari Rhee and William B. Fornia, “Are Most Teachers Better Off With a DB Pension, 401(k), or Cash Balance Plan? The Case of CalSTRS,” Society of Actuaries In the Public Interest Issue 17, pp. 4-10, July 2018, https://www.soa.org/globalassets/assets/library/newsletters/in-public-interest/2018/july/ipi-2018-iss-17-rhee-fornia.pdf.

[14] Rhee & Fornia 2018, op. cit.

[15] For a description of the overall benefit comparison methodology that was used to project retirement income from CalSTRS, CalPERS, and 401(k)s, see Rhee & Fornia 2018 and 2017, op. cit. as well as the Appendix in Nari Rhee and Leon F. Joyner, “Teacher Pensions vs. 401(k)s in Six States,” UC Berkeley Center for Labor Research and Education and National Institute on Retirement Security, 2019. For the purposes of this study, the retirement benefit projection model was updated with the following in order to ensure an apples-to-apples comparison between the pension and 401(k) based on the latest available data: 1) Latest available normal cost estimates. 2) Current published actuarial assumptions for CalSTRS and CalPERS related to mortality and salary growth. 3) Updated 401(k)/Target Date Fund annual gross return estimates based on J.P. Morgan’s 2021 long-term capital market assumptions, with asset-weighted Target Date Fund returns adjusted upward by one percentage point to compensate for the difference in inflation assumptions between J.P. Morgan and CalPERS, and the anticipated recommendation by CalPERS’s actuarial staff to decrease investment return assumption based on forthcoming changes in their capital market assumptions. For 401(k) contributions, the author used the normal costs for CalSTRS and CalPERS, minus a 0.5% estimate for death and disability benefits that are separate from the retirement and termination benefits. Income replacement ratios were calculated in relation to projected salary in the year before retirement. Exiting employees were assumed to retire immediately upon eligibility for commencement of pension retirement benefits.

[16] The 401(k) outcomes differ between teachers covered by CalSTRS and local agency non-safety employees covered by CalPERS due to differences in normal cost (the cost of benefits accrued in the current year). CalSTRS requires higher contribution rates due to higher average life expectancy and a higher percentage of active members on track to collect full career benefits.

[17] Laura D. Quinby and Geoffrey T. Sanzenbacher, “Do Pensions Matter for Recruiting State and Local Workers?,” State and Local Government Review 2020, 52(1): 6-17. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0160323X20942817.

[18] Alicia H. Munnell, Jean-Pierre Aubry, Josh Hurwitz and Laura D. Quinby, “How Retirement Provisions Affect Tenure of State and Local Workers,” State and Local Pension Plans No. 27, Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, November 2012. https://crr.bc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/slp_27-1.pdf.

[19] Rhee & Fornia 2016, 2017, and 2018, op. cit.

[20] Rhee & Fornia 2018, op cit.

[21] Rhee & Joyner 2019, op cit.

[22] Gary Klien, “Marin County’s median house price hits $1.8 million,” The Mercury News, August 30, 2021. https://www.mercurynews.com/2021/08/30/marin-countys-median-house-price-hits-1-8m/. Sonoma County median home price from https://www.realtor.com/realestateandhomes-search/Sonoma-County_CA/overview, accessed 9/15/21.

[23] Income requirement calculated by author, based on a 30-year fixed mortgage, plus taxes and insurance, with a 20% down payment and 3.5% interest rate. Housing costs are generally considered affordable at or below 30% of gross income.

[24] “Economic Impacts of CalPERS Pensions in California, FY 2019-20,” CalPERS, 2021. https://www.calpers.ca.gov/page/about/organization/facts-at-a-glance/economic-impacts-pensions-california. County data accessed at https://www.calpers.ca.gov/page/about/organization/facts-at-a-glance/economic-impacts-ca.

[25] “Economic Impact Study of CalSTRS Benefits in California – Appendix B: Impact by County,” Business Forecasting Center, Eberhardt School of Business, University of the Pacific, August 7, 2013. https://www.calstrs.com/sites/main/files/file-attachments/appendix_b_counties.pdf?1428004250.

[26] “Pensionomics 2021: Measuring the Economic Impact of DB Pension Expenditures (California Fact Sheet),” National Institute on Retirement Security, 2021. https://www.nirsonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/pensionomics2021_ca.pdf.

[27] On the impacts of the shift from DB pensions to DC plans on wealth distribution, see John Sabelhaus and Alice Henriques Volz, “Are Disappearing Employer Pensions Contributing to Rising Wealth Inequality?,” FEDS Notes, February 1, 2019 (revised November 7, 2019). https://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/are-disappearing-employer-pensions-contributing-to-rising-wealth-inequality-20190201.htm. On inequalities in access and ownership of 401(k)/IRA assets, see Monique Morrissey, “Retirement Inequality Chartbook – The State of American Retirement: How 401(k)s have failed most American workers,” Economic Policy Institute, March 3, 2016. https://www.epi.org/publication/retirement-in-america/. On retirement savings inadequacy among California workers, see Nari Rhee, “Half of California Private Sector Workers Have No Retirement Assets,” UC Berkeley Center for Labor Research and Education, July 1, 2021. https://laborcenter.berkeley.edu/california-retirement-savings/.