Paper Girl - understanding across political divides

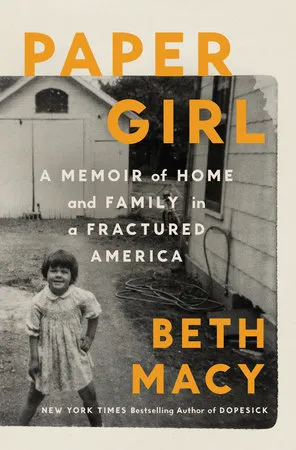

Paper Girl: A Memoir of Home and Family in Fractured America

By Beth Macy, Penguin Books, 2025

As the holidays loom, what’s a safe conversation? With deeply held beliefs about politics, the nation, gender, race, and other issues, casual conversation can quickly turn into an argument.

In PaperGirl, Beth Macy returns to her childhood home in Urbana, Ohio. Now a journalist based in Roanoke, Virginia, but writing extensively for the national media, what’s different back home?

Macy grew up in difficult situations, with an alcoholic father, her family saved by a hard-working, determined mother. Yet she thrived in public school, encouraged by caring teachers, delivered papers for some spending money, and relied on sustaining family and neighborhood networks. Through federal Pell Grants, she attended university, found newspaper positions, and developed a writing career. Not necessarily lucrative positions, but fulfilling.

But what about her classmates, family, and cousins – they were mostly still in Urbana. How had the town changed? Remembering her childhood with a solid Democratic working-class community, why was the community now Trump red? Why were so many children failing school and simply not attending? Where were the solid factory jobs that once supported her community? Why was her old boyfriend, whom she considered the most leftist radical, now a QAnon conspiracy theorist?

Macy immerses herself in her hometown. At kitchen tables, she listens to tales of lives derailed. She rides with a school truancy officer who has to call police for back-up when trying to visit a family, because the property is posted as a “sovereign state” with warnings that anyone approaching will be shot. She painfully learns about the drug addiction, child sexual abuse, and overworked foster care system that haunts the town. Why was her hometown so different from what she remembered?

Economics is one cause – free markets and global trade destroyed the once dependable factory jobs. She blames Democrats for the North American Free Trade Agreement and the World Trade Organization, which promised working people training and upgraded jobs, but instead left shuttered factories.

“The changes wrought on Urbana were a microcosm of the country’s larger failure to address the collapsing economic order brought on by global trade, the transfer of control from public to private, and the growing impotence of what was once a free, fair, and fact-checked local press,” she writes.

As a journalist, she bemoans disappearing newspapers and media, which once shared familiar stories to a community. Newsrooms are shrinking, and people are secluded on internet islands, hearing only what reinforces their beliefs, fact-based or not.

She also looks at her educated contemporaries, moored on blue islands, oblivious to what working people, farmers, and small towns have lost, writing off these populations as “deplorables.” Where is the dialogue between political factions to find, if not common ground, at least mutual respect and understanding?

Macy deftly blends the sometimes heartbreaking stories from her hometown with a macro view of why so many institutions are failing and why our economy only makes the rich richer. Political manipulation, stirring people over gender and race, rather than the real economic destruction, leaves people angry and isolated, looking for a savior whose rhetoric promises greatness but rarely delivers.

To understand our current politics and culture, reading and learning about political leadership is one challenge; more appropriate is knocking on doors and learning about people’s real-life struggles, which is the real eye-opener, and perhaps, a way to listen and build human understanding. Macy well succeeds in that effort and opens doors that too few dare to peer into.

- Mike Matejka