"Goliath at Sunset" novel challenges both the company and the union

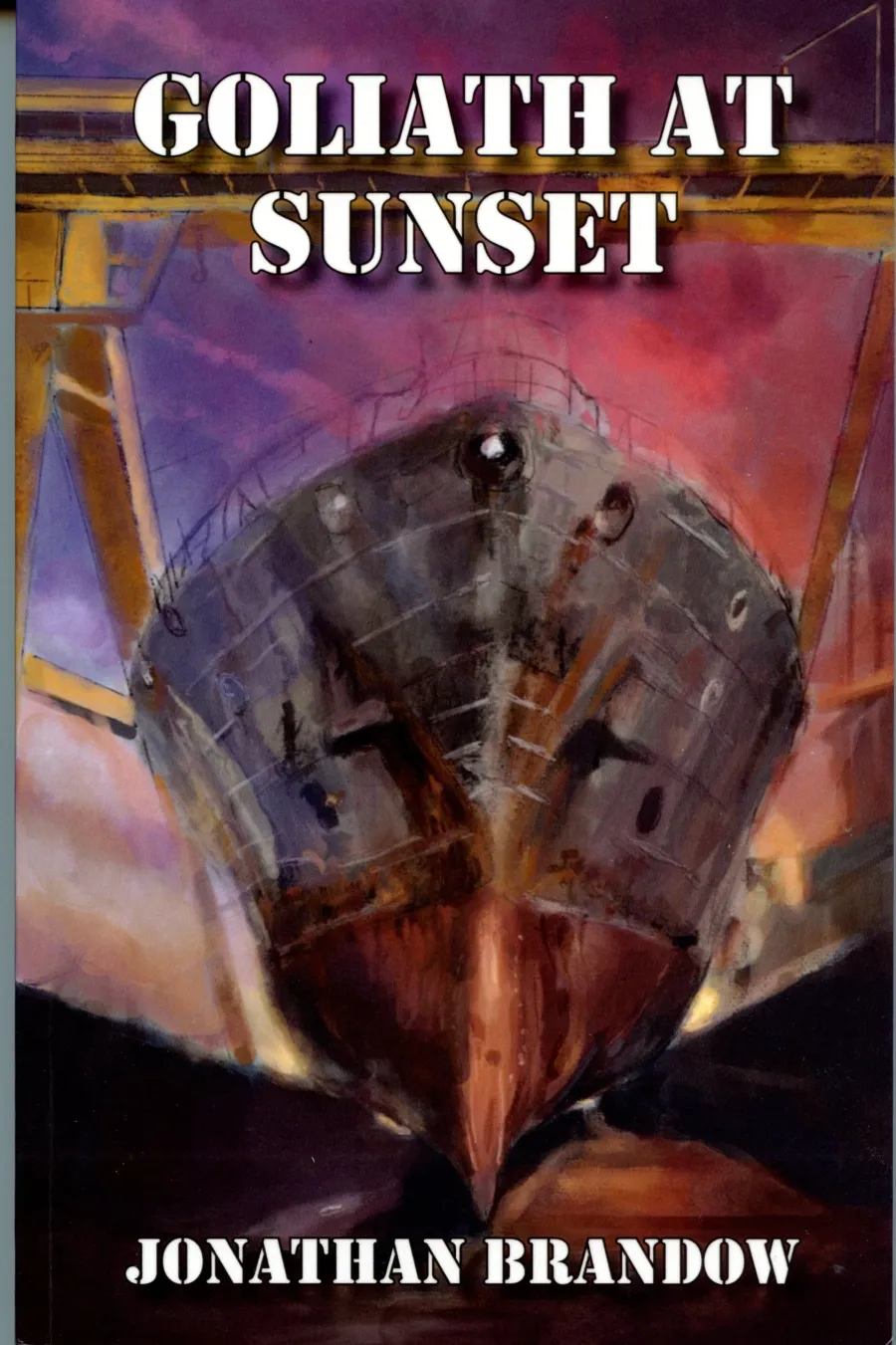

Goliath at Sunset

By Jonathan Brandow

Hardball Press, 2025

The 1970s were a seething time in U.S. history. The Vietnam War was winding down while inflation was nibbling away at paychecks. Federal settlements broke workplace segregation, giving African Americans, Latinos, and women their first bite at decent, union jobs. The 1950s triumvirate – big business, big government, and big labor – would soon see labor’s leg kicked out as anti-union campaigns and trade wars wreaked havoc on U.S. jobs.

Boston, the American Revolution’s breeding ground, in the 1970s was seething with racial tension, as mandatory school busing divided the community into warring factions.

Jonathan Brandow’s first novel, Goliath at Sunset, features a returning Vietnam vet, Mike Shea, finding work as a shipyard welder. A child of the projects, his mother died from a police beating while trying to win a new contract along with her Dominican electronics factory co-workers. From his mother’s experience and jungle duty, Shea learned that racism was a false proposition. His shipyard apprenticeship classes featured diversity, and he was soon riding the bus with African American workers for their late shift clock-in.

Safety issues, race, and gender divisions soon got under his skin. Where was the union? The union steward seemed ineffectual, and the union hierarchy, driven about in black Cadillacs, seemed oblivious to second shift complaints.

Shea soon wins a rebel’s reputation. He dates an African American fellow worker, crossing a racial boundary that raises eyebrows. The older, World War II-era workers seemed oblivious to the younger workers’ complaints. They seemed content to keep their heads down, grumble, living for that pension and the fabled two-week vacation.

Shea builds a coalition and soon is elected a union steward, roaming the workplace, fighting for safety enforcement, standing up for the diverse workforce, demanding that ugly racist graffiti be scrubbed from restroom walls.

For all his militance, there’s always a hard lesson awaiting. Building trust is fraught with traps and lingering resentments. Both management and union leadership are always one step ahead, as he learns the union leaders have forged backdoor deals to protect workers, all creating a drudging loyalty within the workforce.

Shea is left scrambling. The union pulls him up on charges, which are quickly quashed as rank-and-file members rebel. Despite this, he is increasingly frustrated, his romance a victim of his own fears and anger.

And just when it seems he’s gaining legitimacy with the union, the Iranian hostage crisis kills tanker jobs. The company and the union triumph, promising laid-off workers more jobs, repairing wrecked Japanese ships. The company cracks down on rules, forces overtime, and pushes the workforce into a safety catastrophe on a hulking tanker wreck.

Brandow captures the 1970s tension and its possibilities well. Can this young, diverse workforce, fresh from Vietnam, gain decent jobs, create a more responsive, worker-centered union?

While Shea and his cohort challenge both entrenched union leadership and the company, global capitalism has a different plan. Cost-cutting, rule enforcement, skimming safety, and mass layoffs soon raised their ugly head, as the 1970s ushered in an era of failing union power, middle-class collapse, and international corporate dominance.

Brandow weaves a telling text, capturing diverse voices, youthful energy, and a shipyard’s vocabulary and slang. The author spent nine years in a shipyard and also as a union officer. Even if the reader is not a welder, the workplace’s cadence and challenges, along with the pride in craft, shines through. The reader feels both Shea’s impatience for change, while facing a world that is always one step ahead of him. “Goliath” is the giant crane that looms over the shipyard, reflecting both the opportunities and the casualties ahead. For an authentic working-class novel, one can’t go wrong with Goliath at Sunset.

Mike Matejka