Book review - Public schools vital to democracy

Public Education & Social Reform: a History of the Illinois Education Association

By Tom Suhrbur, University of Illinois Press, 2025

Where do we learn to listen, consider multiple ideas, and expand our knowledge? Hopefully, in a school classroom.

Tom Suhrbur’s Public Education is a very thorough overview of the Illinois Education Association’s (IEA) evolution, but also the social role and importance of public education.

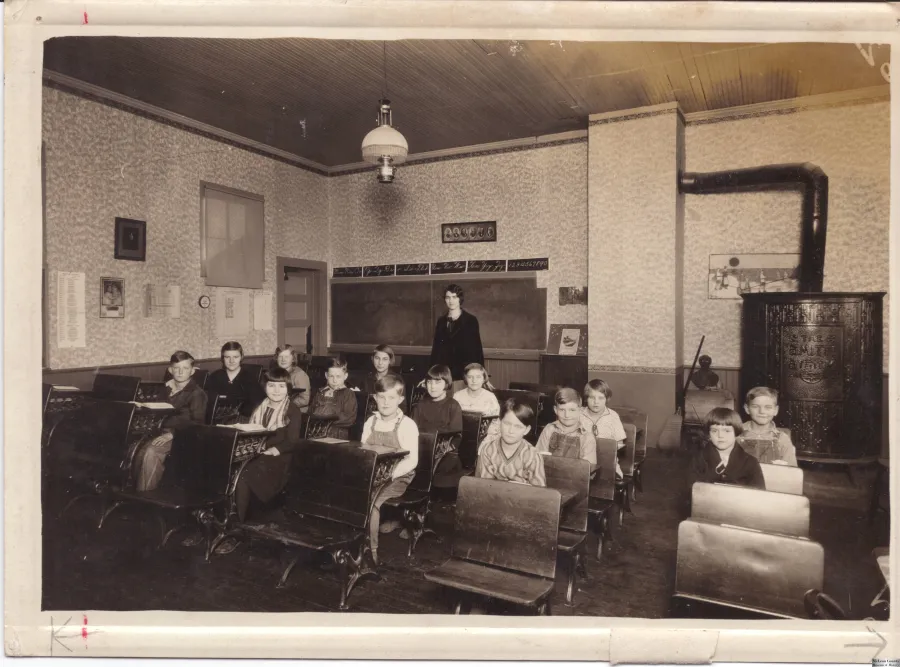

The book begins with Illinois’ frontier days, where education was usually a local prerogative, needing willing parents who would support a rudimentary log cabin school and a teacher’s salary. Education was mandated in early legislation but poorly financed, dependent upon local support, rather than a state system – a challenge that continues today.

Educators organized before the Civil War (1861-1865) for a secular school system with professional teachers. Local custom often required teachers to follow Protestant religious norms and teach from scripture. Early teaching professionals found this restrictive and limited schools to certain faith traditions. Their support for credentialing teachers led to the establishment of Illinois’ first teaching college, or normal school, in Bloomington and then Normal in 1857.

School funding and teacher certification were long-running conflicts, particularly when education funding was often the first appropriation cut and was subject to campaigns by low-tax adherents. Illinois’s schools' dependence on local property taxes created significant educational disparities between high-income and working-class communities.

Teachers looked around at other professions and trades and realized that union organization could gain power, not just for teachers, but for the children they served. Chicago teachers recognized this early, forming what would become Local 1 of the American Federation of Teachers (AFT). This union, led by teacher Margaret Haley, not only fought for better working conditions but also challenged Chicago’s lax property tax collection practices, which were detrimental to education.

The IEA saw itself as a professional association, including school administrators in its membership, with a primary function lobbying the legislature for school reforms and funding. By the 1960s and 1970s, the AFT was organizing local unions throughout the state, improving members’ conditions.

It was not until the 1970s that the IEA reoriented itself as a union, although it was initially reluctant to use that term. Its early efforts were marred by internal conflicts with its own staff, who had formed their own union. Throughout the 1970s and the 1980s, both the IEA and the AFT formed rival organizations in school districts, often battling in representational elections at each contract negotiation.

The 1983 Illinois Educational Labor Relations Act gave school employees a clear vehicle for gaining union recognition. No longer were teacher union officers jailed for trying to organize a union and win contracts. The IEA and the AFT were fierce rivals for organizing new union locals. The IEA’s parent, the National Education Association, and the AFT flirted with a merger and agreed to joint actions but remained separate. In 1995, the IEA and the Illinois Federation of Teachers agreed to “no raids,” respecting each other’s local unions.

This book is worth reading simply to see how so many early issues resonate today. School funding, teaching religious programs in public schools, and school workers’ right to organize and live decently echo through the decades. Suhrbur has written a very detailed and complete history of Illinois education and teachers’ efforts to uplift their communities and profession.