1941 - worker turmoil in Disney's studios

The name Disney conjures amusement parks, animated characters and memorable music. What about all the backstage people who hand-draw, color and paint those magical cartoons? Just as low-paid internet “contact creators” are organizing today, so did Disney workers 81 years ago.

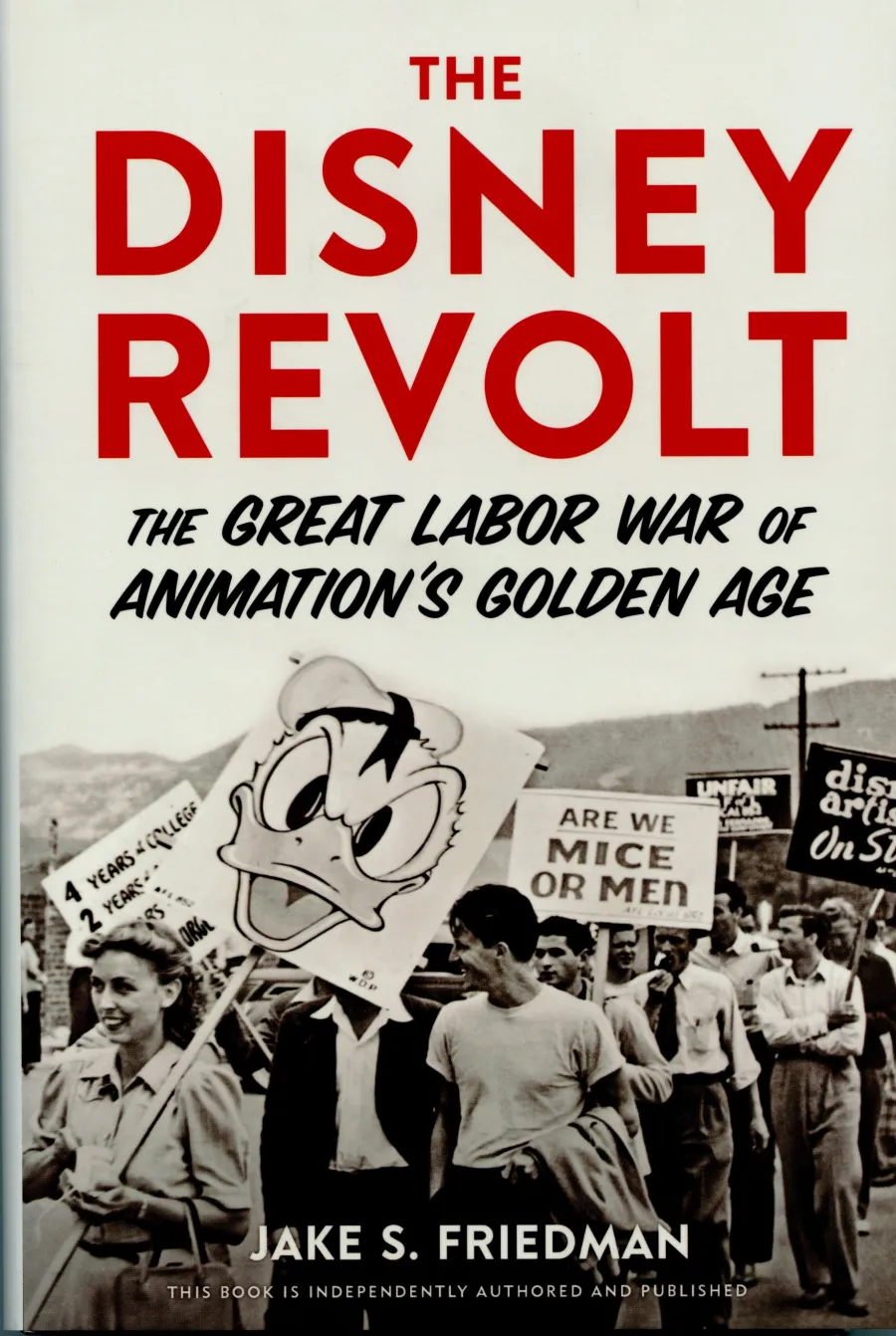

Cartoon animation required artists by the hundreds, drawing and coloring individual, 24 frames per second. These workers organized, a story well told in The Disney Revolt.

Walt Disney was a driven and persistent workaholic. As his studio grew and the workforce expanded, workers were underpaid and driven to produce.

Besides Walt Disney, the book’s other key character is Art Babbitt, an early, innovative Disney animator who took his craft seriously.

Disney practiced profit-sharing with Babbitt and his early studio crews, rewarded for their efforts. The first feature length animated film, Snow White, marked a turning point. Disney went deeply in debt to produce the film, pushing his workers to produce, promising profit-sharing later. The film was highly profitable but Disney spent the money to build an even larger studio, not rewarding his workers. The next two feature films, Pinochio and Fantasia, fared poorly in their original release.

Other animators, like Warner Brothers, were unionized and paying their employees higher wages. Frustrated Disney workers organized the Screen Cartoonists Guild. When Disney refused to recognize their union they walked out on May 28, 1941, staying in the streets until August 2 to win their contract.

The strike ended but bitter feelings remained. Disney rarely mentioned the strike and remained close to his picket line crossing loyalists. Babbitt served in the U.S. Marine Corps during World War II and returned to Disney, where he was shunned, given few assignments. With a large cash payout to settle his grievance, Babbitt resigned in 1947 and went to work for other studios and taught university classes in animation.

Walt Disney died in 1966. On his death bed in 1992, Babbitt received a Fantasia video from Roy Disney, acknowledging Babbitt’s contributions. In 2007 Disney studios recognized Babbitt as a “Disney Legend.”

A third thread running through the book is union corruption. Chicago’s Willie Bioff, a Capone crony, rose to power in the International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE). With IATSE President George Browne as the front, Bioff signing sweetheart deals first with theater chains and studios, promising no “labor troubles” in return for payoffs. Bioff circled Hollywood and met secretly with Disney to instigate a sweetheart deal to thwart the Cartoonists’ strike.

Bioff and Browne were found guilty of extorting $1.2 million from studios in November 1941. Bioff turned state’s evidence and helped break the Capone syndicate’s operation. He died on November 4, 1955, when his car was dynamited and exploded.

This book is a unique blend, sharing early animation technology, an ignored Disney backstory, creative workers and their poorly paid labor and a union shark circling for self-profit. It’s an enjoyable and easy read, well-illustrated with photos and cartoons.

Book Review

The Disney Revolt: The Great Labor War of Animation’s Golden Age

By Jake S. Friedman

Chicago Review Press, 2022

By Mike Matejka